Lucknow or Zaike: A City Remembered Through Taste

Among the many cities that possess a distinct history and cultural identity, Lucknow stands apart with quiet confidence. It occupies a dignified place in India’s cultural and literary imagination, where etiquette is inherited, language is polished like silver, and food is treated not as indulgence, but as heritage.

Lucknow’s culinary legacy is not merely about eating well; it is about refinement, patience, and poetry on a plate. Each dish carries centuries of memory, shaped by royal dastarkhwans, slow fires, and narrow bylanes where aroma becomes a language of its own.

Understanding Lucknow, Through a Lucknowi

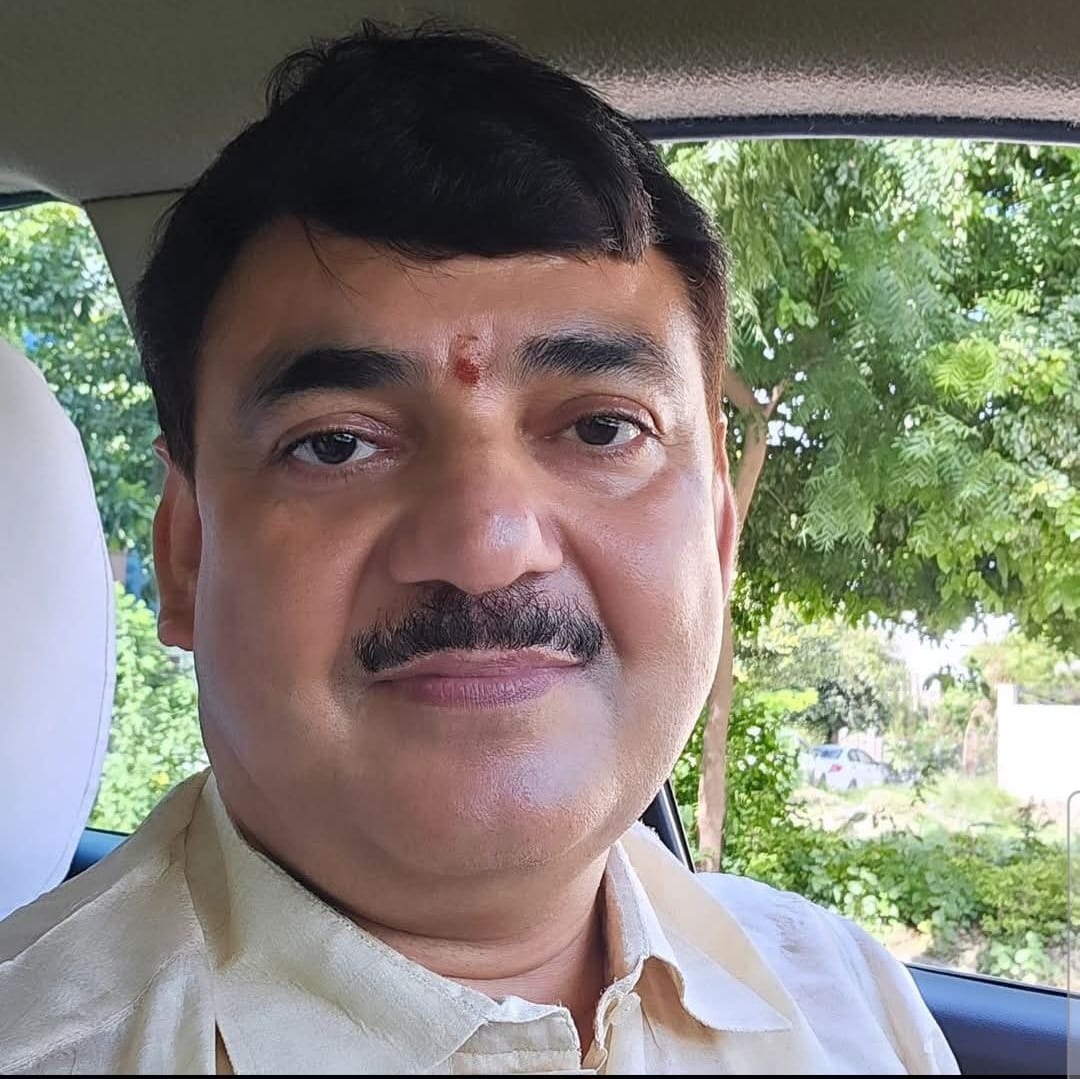

My journey into Awadhi cuisine began not with a restaurant, but with a person my dearest friend Ayan Ahmad. A Geologist by profession, currently working in kuwait, yet born and raised in Lucknow, Ayan bhai carries the city within him. To understand a city deeply, one must walk it with someone who belongs to it. And to understand Lucknow, there is no better guide than a Lucknowi himself.

With Ayan bhai, Lucknow revealed itself differently, not as a postcard city, but as a living organism. The subtleties he showed me, the fragrance of food drifting through old lanes, the pauses between conversations, the unspoken rules of taste, are things only locals truly understand. Whether it was the flavour of a dish or the curve of a forgotten gali, every detail felt intimate, almost guarded.

Idrees Biryani, Where Time Cooks Slowly

When Ayan bhai casually mentioned that we would need to reach Idrees Biryani an hour early, I assumed it was because of crowds. What I witnessed instead was something far more extraordinary.

Established in 1968, in the bustling lanes of Chowk, Idrees is not a place that reheats food, it cooks afresh every single hour. Each batch of biryani (or more precisely, yakhni pulao) is prepared in large copper deghs, placed over coal-fired bhattis. In an age dominated by gas stoves and shortcuts, Idrees continues to cook on pathar ka koyla, maintaining a consistency that borders on devotion.

Watching the biryani being made felt like witnessing a ritual. The rice is fragrant, the meat impossibly tender, and the process deeply hygienic despite its old-world setup. For a moment, I forgot the present year 2026 and felt transported into a slower, more intentional time.

The Process, Patience Over Performance

Idrees’ biryani is known for its slightly greasy, aromatic yakhni pulao never layered like Hyderabadi biryani, never aggressively spiced. Each degh takes nearly three hours to prepare, and the kitchen produces 20-22 deghs daily, each one identical in spirit and flavour.

The yakhni begins with mutton neck pieces, chosen for their depth, simmered with cardamom, mace, and gentle spices. The meat is massaged with milk and malai, lending softness rather than heaviness. Rice, partially cooked with whole spices, is layered with the broth and meat, then sealed for dum, allowing aroma to lead before taste follows.

The final dish is warm-toned with zafrani and makhani hues, served alongside qorma and vinegar-soaked onions. What emerges is balance, not excess, not austerity.

Though the world calls it biryani, Abu Bakr Idrees, who has run the kitchen for over three decades, insists it is yakhni pulao. For him, precision matters. In an era where definitions blur for convenience, Idrees refuses dilution.

Faith, Food, and Legacy

Located at Pata Nala, Raja Bazaar, the story of Idrees is as spiritual as it is culinary. Abu Bakr often says, “I cook with good intent. I cook the food, Allah adds taste to it.” The legacy began with his father, Mohammad Idrees, who trained under Haji Abdul Raheem for 25 years before starting his own establishment.

Despite rising costs and changing food trends, the philosophy remains unchanged. Abu Bakr speaks candidly about inflation, about people who can only look longingly at food today, and even jokes about the modern obsession with “low-fat” meals, remarking that charm, too, requires nourishment.

The shop itself is very old, tucked into a narrow space with no proper seating to speak of. Yet what it lacks in comfort, it makes up for in character. The service is rooted in adab-o-adaab and an inherited sense of tehzeeb. When you sit at the outdoor table, a fresh paper dastarkhwan is always laid out before the food arrives, quietly, respectfully, as if dignity itself is being served first.

UNESCO and the World’s Recognition

In October 2025, UNESCO designated Lucknow as a “Creative City of Gastronomy”, making it the second Indian city after Hyderabad to receive this honour. The recognition celebrated Lucknow’s centuries-old Awadhi cuisine, its kebabs, slow-cooked gravies, biryanis, and street food, crafted with restraint rather than spectacle.

As the announcement echoed across the city, it felt less like news and more like overdue acknowledgment.

Lucknow is not remembered only through monuments or poetry, it is remembered through zaikha, through patience, and through people who refuse to rush tradition. To eat in Lucknow is to listen, to pause, and to understand that some cities do not reveal themselves easily.

A Final Lesson in Integrity

The experience found its quiet climax in a moment I will never forget. When our turn finally came, a freshly cooked patila was brought forward and placed before Hammad bhai. He paused. Then, in his unmistakable Awadhi tongue, he called out sharply to the worker—and sent the vessel back.

“Abhi dum aur lagega,” he said. The biryani is not ready.

Nearly eighty people stood waiting in line, many of them already an hour deep into patience. And yet, without hesitation, the owner refused to serve what he believed was unfinished. No apology, no performance, only conviction. The degh returned to the coal, dignity intact.

In that instant, I understood something deeper than flavour. What was being protected was not just a recipe, but a principle. In a world eager to compromise, this quiet refusal, this insistence on completeness, became the most honest culinary experience of my life.

Popular Categories

Read More Articles

Business

What's Up With WhatsApp? by Prateek Shukla February 9, 2026Entertainment

Reviving the Sounds of Awadh: Folk Singer Sarita Tiwari to Provide Free Training to Rural Women and Girls by Awadh 360° Desk February 7, 2026India

रिसर्च एंड डेवलपमेंट योजना’ के तहत सेंटर ऑफ एक्सीलेंस गठन हेतु विशेषज्ञ समितियां गठित by Awadh 360° Desk February 6, 2026Travel and Tourism

The Grid of Greatness: Why Chandigarh is India’s Urban North Star by Mohammed M. Raza February 6, 2026